|

|

|

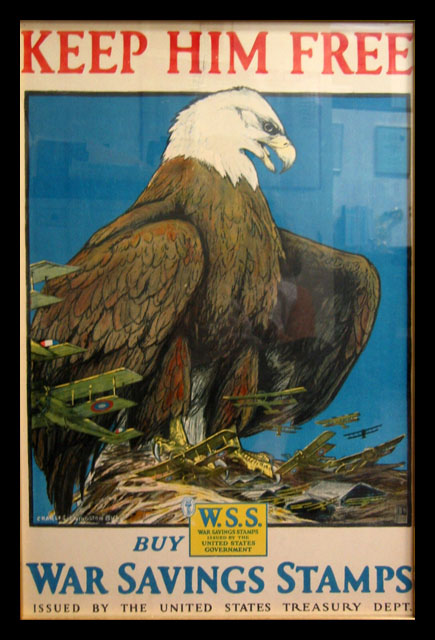

Title: Keep Him Free – War Savings Stamps

Description: The proud American eagle stands vigilant over its unusual brood—a nestful of airplane hangars and biplanes. Proud, strong, and resolute, the momma bird, symbolizes U.S. national determination and seeks to stir the parental instinct in all that gaze upon the poster. The image implies that, fed on War Savings Stamps, the American eagle and its young would take to the skies in defense of the nation, an image of aggressive patriotism that would hopefully motive the viewers to use their own funds to contribute to the war effort. This poster, by noted nature artist Charles Livingston Bull (1874-1932), was produced for the Nation War Savings Committee’s War Saving Stamps program (WSS). The WSS, inaugurated in 1917, sought to redirect consumers’ dollars from personal nonessential spending to the U.S. government’s war needs. Based on a similar British program, the War Savings program had two goals, First was to raise money for America’s war effort through the purchase of the Savings Stamps--essentially promissory notes in varying amounts. One could buy Thrift Stamps for twenty-five cents and War Savings Stamps that were worth five dollars, the stamps being sold in stores, theaters, sidewalk booths, and hotels. |

Both these stamps were “discounted promissory notes,” and could be saved and redeemed a year later for a slightly higher value, based on a set interest rate. Each year the cycle would start over, with new stamps being made available for purchase with their redemption possible after another year. By the close of the program, the U.S. government had raised over a billion dollars through the War Savings Stamp effort. The WSS’s second goal was to encourage workers on the home front to funnel their earnings back into the war effort. Well-paid and in demand, because the war had depleted so much of the labor force, war workers found themselves with a sudden influx of expendable income, tempting many to purchase luxury goods. The WSS sought to redirect this cash stream back to the war effort. When workers bought WSS stamps instead of consumer products, they supported the war in two major ways—directly adding to the war coffers and indirectly, by lessening the demand for nonessentials and thus freeing up the raw materials, used to make these nonessentials, for war production. Numerous posters were produced for this drive. Themes ranged from Uncle Sam encouraging children to buy the stamps to Joan of Arc depicted calling on American women to contribute. Charles Livingston Bull’s poster shown here utilizes a classic American image, the bald eagle. Bull, born in New York state, had studied both drafting and taxidermy in school and from his youth expressed a great interest in and affection for animals. His talent led him to earn a post as the Chief Taxidermist of the National Museum (now the Smithsonian Institution) in Washington, D.C., where he also sketched animals at the National Zoo and took classes at the Corcoran Gallery. Later working in New York City, Bull would sketch at the Bronx Zoo and was a successful illustrator, providing art for such publications as The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, and The Country Gentleman. Drawing stylistically on both the Art Nouveau and the Arts and Crafts movements, as well as Japanese prints (a common influence on artists of the period), Bull utilized both Art Nouveau’s curvilinear lines and the use of outlines to define his shapes, typical of the Arts and Crafts artists. His works usually feature strong lines and a flat composition, with cropping to emphasize drama and movement. By the end of his career, Bull was viewed as America’s preeminent wildlife artist, and one of the best in the world. The publisher, Ketterlinus, was an old Philadelphia firm, the first “Ketterlinus Printing House” having been built in 1855. A replacement building constructed in 1905 was described as “the largest reinforced concrete building in Philadelphia.” In the 1960s the building was demolished to make way for the Philadelphia Mint. An 1870 advertisement for the firm promises engraving and embossing, as well as “Lithographic and Letterpress Printing of Every Description. |

|